Hello, I’m excited that Jules from

has agreed to write a guest post this week as part of the series of Picture This. It’s a wonderfully serendipitous story about a place I love and an artist that never fails to inspire me.What is the picture of?

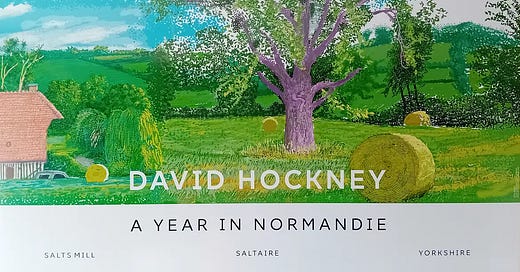

This is one of a series of iPad paintings of Normandy that was made by the artist David Hockney while he was living and working in France during the coronavirus pandemic. It’s a poster from his art gallery at Salts Mill in Saltaire, West Yorkshire, which I visited with my husband on 6th June 2022. It hangs on the chimney breast in my living room, and when I sit in my usual seat it is facing me, so I look at it most every day.

Hockney is a prolific artist and an able communicator, and I’ve watched several documentaries by and about him over many years. I’ve learnt a lot from him. Over a long career he has used many different types of media, exploring old techniques and embracing new ones, including chemical and digital photography, iPhones and iPads. I am fascinated by his experiments with the potentially confining notion of perspective. He emphasises the importance of looking and seeing, and how the eye perceives its environment. He summed it up in this comment from a 2001 BBC Omnibus documentary, David Hockney - Secret Knowledge:

“Most people don’t look much. I mean, they scan the ground in front of them so they can move around. Well, I’ve spent my life looking.”

Why did you choose it?

Primarily because it’s an uplifting image of a tranquil, bucolic scene. It’s beautiful, and it was made by someone whose work I have admired for as long as I can remember. It is also a reminder of one of the most memorable moments in my life; a moment when I came face-to-face with the artist.

The 1853 art gallery at Salts Mill was established to house some of Hockney’s work, and it sits on the outskirts of Bradford where he was born in 1937. When I found out about it, I decided to visit at the first opportunity.

We were not far away from Saltaire when we took a wrong turn. It delayed us by about 10 minutes. This seemingly insignificant detail was more important than we realised.

When we arrived at the gallery, we headed straight to the top floor of the building to see A Year in Normandie, a 90.75-metre-long frieze recording the changing seasons in and around the artist’s garden at his home in the Pays d’Auge.

After looking at the whole piece, Hockney’s largest ever picture, I was so captivated by it that I decided to view it a second time before going to watch an accompanying film being played on a loop in a side-room. We set off again. While I hung back, making the most of this last chance to absorb the ravishing images, my husband went on ahead.

I was about two thirds of the way round when I noticed a man in a wheelchair. He had paused in front of a section of the frieze and was examining its surface very closely, almost as if he was having trouble seeing it. Not wishing to crowd him and his companion, I walked around them and continued onwards, taking a final look at the last few pictures. As I reached the end, I saw my husband walking towards me. He was smiling, and his emphatic expression told me that something unusual was afoot.

“Look behind you. Now!”

I turned around and saw the man in the wheelchair facing me. I was astonished. I was looking at the smiling face of David Hockney. He was wearing his trademark white cap and a natty suit and tie. I thought I was hallucinating.

Almost immediately the atmosphere in the room started to shift. A woman approached him with a baby. Another accidentally jostled him as she tried to get a selfie, and he looked a little startled. We stood well back as a crowd started to gather. I waited a few more seconds, just to allow my brain to comprehend the fact that I was looking at a man whose work has meant so much to me, then turned away.

We ducked into the empty video room where I tried to catch my breath and turn my attention to the film, but suddenly there was movement just behind us. A small group entered and we moved aside to make way for the wheelchair. My heart was pounding, and I resisted an irrational impulse to break into applause.

I am prone to stupefaction when over-excited, but my husband is not so easily overwhelmed.

“Hi” he said easily, smiling happily at our greatest living artist. Our greatest living artist beamed back.

The group moved further into the room as if intending to watch the film, but an elderly man came in, made a beeline for Hockney and struck up a conversation. It didn’t look as though the artist was going to be allowed to watch his film after all, and he and his friends wisely made a discreet exit. We stayed on to watch the video, but I was in the grip of brain paralysis, and I can barely remember anything about it.

It was a most unlikely coincidence. At that time, Hockney was not resident in the UK, yet he was at the gallery on the day we chanced to visit. Had we not got lost on the way there, or if we’d left after our first viewing of A Year in Normandie, we may never have known that he was in the building.

How does it make you feel? What is the significance of it?

It seems to me that an array of factors might potentially have influenced the creation of this image - factors like the artist’s skill, the tools he has used, his life experience, his ocular capacities, his emotions, his perception of colour, even his sense of his own mortality. What would the image have looked like if he’d created it in his twenties? Of course, he would not have been using digital media, but might it have differed in other ways? Considering the transformations that occur within a human being over the span of a long life, and how this might influence an artist, I think it’s likely.

When I look at this picture, I feel my eyes fill with light. I feel the quietude, or rather the gentle sounds of nature. Some days I feel the distant sounds of livestock, the vehicle firing up, or some unseen farm machinery droning in a distant field. I feel warmth, and the possibility of a gentle breeze, or no breeze at all. Occasionally I feel the sound of the chatter of unseen people who may be just outside the parameters of the picture.

We are looking at an image that in one sense has taken a relatively short time to make, and in another, decades to realise. The refining of the artist’s skill over such a long period of time means that we are privileged to be looking at the result of over eighty years of accumulated knowledge and practice.

The image is presented here as a single, self-contained picture, but it is also one of a series of images assembled in sequence to create a single artwork.

It’s an inexpensive reproduction of a painting worth many thousands of pounds; the frame that protects it cost eight times more than the picture itself.

It also functions as a poster advertising an art gallery. Several different images were used in this series of posters, and this was the one I liked best. If you have one of these posters, you may have a different image hanging on your wall.

Finally, for me, this picture is a reminder of a dazzling work of art, and of a June day in 2022 when I had an unexpected brush with genius.

Yes the restaurant there is good! We had a bite to eat afterwards and I kept the napkin. It had a picture of his dachshund Stanley on it!

Lovely story Jules and Margaret ! ☺ so descriptive, and great collaboration ! Perhaps they'll be more in the future 🤩 A truly fabulous and very versatile artist.