What is the picture of?

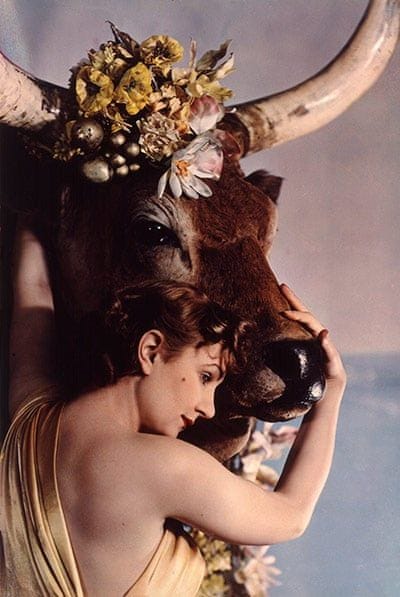

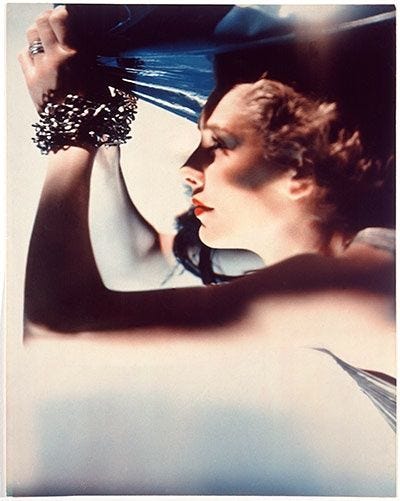

It could have been Persephone, Medusa, or Europa with her garlanded bull, but there has always been something about this portrait of Aileen Balcon that has sucked me in. Minerva was the Roman goddess of wisdom, war, arts and crafts, schools, and justice. The sumptuous folds of her primrose silk robe sing against the patina of the helmet and the feathered owl balancing on the cold metal of her gun. Her pallor is cold, she could be a statue, but then there is the red lip giving her life.

Aileen was the wife of producer Michael Balcon, who was responsible for classic films including The Lavender Hill Mob and The 39 Steps, which came out the same year as this photograph. Michael and Aileen had a daughter Jill who became an actress and married the future poet laureate Cecil Day Lewis – and they had a son, Daniel Day Lewis.

I suspect that Aileen had more than a passing understanding of production herself. Working with the photographer Yevonde they played around with props both ancient and modern, to create these wonderful images of Minerva.

In 1935, the photographer Yevonde Philone Middleton embarked on a series of photographs capturing society ladies in stunning Vivex colour inspired by their attendance at The Olympian Ball at Claridge’s, where The Bright Young Things arrived in costumes designed by the likes of Cecil Beaton, inspired by Ancient Greece.

Fauns and other nymphs were seen cavorting in the corridors of the art deco hotel at the charity gala and this picture-perfect Bacchanalia was enough to inspire Yevonde to cast the society ladies as mythical goddesses. She used incredible props, costumes, and techniques to create something individual and new.

‘Be original or die would be a good moto for photographers to adopt. Let them put life and colour into their work.’

Why did you choose it?

I first saw the images of The Goddesses around twenty years ago and I immediately fell in love. Her work is adventurous, playful, and modern. It is also incredibly skilled. She portrayed women with strength and humour in the most exquisite colour. They are fantastical, beautiful images.

Yevonde Cumbers was born in 1893 in Streatham London and was an early supporter of the women’s suffrage movement. In 1910 she secured a job with Lena Connell the suffragette photographer at her studio – but she didn’t take it, choosing to become an apprentice with the leading society photographer at the time, Lallie Charles.

On her 21st birthday she received money from her father, which allowed her to open her own studio and Madame Yevonde was born, conjuring up images of a fortune teller or at the very least of her hiding under the cloak of a camera. Photography was a means for her to carve out her independence but even her early images were extremely accomplished.

Rather than capturing society ladies gazing into the middle distance wondering what they were having for dinner she injected sass into the portraits. She was commissioned by the illustrated press, regularly working for magazines like Tatler and The Sketch. As her reputation grew, she also took on advertising campaigns. It is the combination of these two things that I think led to her early editorial style.

Her early career peaked with her experimentation of colour. She was the first woman to lecture at the Professional Photographers’ Association. By 1932 Madame Yevonde’s work was shown at the first ever exhibition of colour photography in Britain at the Albany Gallery on Sackville Street. She was a pioneer of the medium and an advocate for the merits of it as a fine art form, giving lectures, and interviews on the subject at a time when it was dismissed by many of her contemporaries. Henri Cartier Bresson is believed to have said ‘colour is bullshit.’ Yevonde on the other hand exclaimed:

‘Hurrah, we are in for exciting times. Red hair, uniforms, exquisite complexions, and coloured fingernails come into their own. If we are going to have colour photographs, for heaven’s sake let’s have a riot of colour.’

What is its significance?

The Vivex colour process was introduced in the early 1930s by Colour Photographs of Willesden. It was expensive, requiring three panchromatic glass plate negatives exposed through coloured filters for printing with yellow, magenta, and cyan. Yevonde mastered the process and then broke the rules taking it further by using filters such as green cellophane over the lens. She created her very own look.

Aside from photographing society ladies, Yevonde’s work is vast including still life fantasies with more than a nod to the surrealists Man Ray and Lee Miller. By the time war broke out in 1939 Vivex had ceased trading and Yevonde worked in black and white, continuing to experiment with surrealism. In the 1960s her experimentation led her to the technique of solarisation.

She continued to work and even had a studio in Manchester’s St Ann’s Square for a short time, until her death in 1975. Her work was clearly an influence on photographers as diverse as Pierre et Gilles and Tim Walker. I don’t think we would have modern-day fashion editorial without her pioneering images.

The National Portrait Gallery acquired 2000 tri-colour separation negatives by Yevonde in 2021, the most significant colour photography archive by a woman to date. They hosted a major exhibition Yevonde: Life and Colour in 2023.

Other sources include Vogue and Tatler.

Thank you for reading. Picture This is a series that I run inspired by the fact that I deleted my Instagram account and John Berger’s seminal work Ways of Seeing. You can read the original post here and several guest posts.

On Andrew Wyeth A Guest Post by Katy Wheatley

Fascinating post. The warmth and richness of the color is what makes film superior to digital (in my opinion). I also love the lighting. Photography is painting with light, and the beautiful glow down the owl is masterful.

Fascinating, Margaret. Did not know about Madame Yevonde. (Or the connection with the Day Lewises!)